- Home

- About Us

- The Team / Contact Us

- Books and Resources

- Privacy Policy

- Nonprofit Employer of Choice Award

The following is an excerpt from the new book, The Intrepid Nonprofit: Strategies for Success in Turbulent Times, by Tim Plumptre and available from Civil Sector Press.

The following is an excerpt from the new book, The Intrepid Nonprofit: Strategies for Success in Turbulent Times, by Tim Plumptre and available from Civil Sector Press.

Today’s environment keeps shifting in ways that are difficult or simply impossible to predict. The intrepid nonprofit may survive and even thrive despite this, but to do so will require initiative, imagination, and a willingness to persist when the going gets tough. It is also likely to require a strategy, or a blend of strategies, that holds the promise of success. What are those strategies?

Some contemporary writers posit that the current landscape is so challenging that nothing less than a fundamental and dramatic change to conventional structures and practices is required. Perhaps they are right. However, the executive directors or CEOs of most nonprofits I am familiar with would be very unlikely to welcome “a complete rethinking” of their organization. Reorganizations are always time-consuming and upsetting, and very often they deliver less than they promise. Also, they tend to consume a very large amount of executive time—time that would normally be devoted to running the organization. Many nonprofit boards would have difficulty according their executive director a holiday from day-to-day leadership responsibilities so that the incumbent’s energies could be almost entirely devoted to a general reorganization or rethinking of the organization.

In these circumstances, it seems to me that the practical place to start may be with an assessment of the need for change: What’s not working? Where are the gaps? What are the threats and challenges facing your particular organization? This initial step is one that most nonprofits would do well to take in the near future if they haven’t already. “Business as usual” is unlikely to be an adequate response to a shifting, evolving business context. An assessment may or may not reveal a need for drastic alterations to existing structures or processes, but it would certainly provide the organization with a basis for charting the way forward.

Following this assessment, the organization should ask what it could do to fix problems, address gaps, or meet new challenges that have become apparent—and what approach to change would be feasible given its circumstances and resources. In many instances, a stepwise strategy may make sense, whereby changes are implemented over time and at a pace that can be accommodated while allowing the organization to continue carrying out its mission.

Furthermore, if there is one maxim about both governance and management that bears repeating, it is that there is no such thing as a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Every organization is unique, every organization’s circumstances are different, and each nonprofit will need to make its own judgements about what kinds of adjustments or restructuring are necessary to confront the turbulence in its environment.

Because of this, unlike some other authors, in what follows I have resisted the temptation to assert that every organization must do this or that. Rather, I have provided below a kind of menu of approaches or strategies that I hope will be helpful to nonprofits wondering how to move ahead. These are informed by a fairly extensive review of relevant literature, complemented by over fifty interviews with nonprofit leaders, consultants, and executives in foundations or umbrella organizations for the sector, plus my own experience over at least a couple of decades.

A Focused, Clear Mission

Organizations that are coping well with this turbulent environment tend to be lucidly clear with respect to their mission and the results they hope to achieve through their work. Take the example of Pathways to Education Canada, a nonprofit organization with the following mission: “For youth in low-income communities, Pathways to Education provides the resources and network of support to graduate from high school and build the foundation for a successful future.” 1 A pathway addresses systemic barriers to education by providing leadership, expertise, and a community-based wraparound program proven to lower dropout rates. Its program has been shown to diminish high school dropout rates by as much as 75 percent. The organization has achieved exceptional growth over the past fifteen years, with an ongoing record of sustaining corporate, foundation, and government support. It is a recipient of the Imagine Canada Trustmark. A study of the Pathways Program by the Boston Consulting Group in 2007 reportedly revealed, “[F]or every one dollar invested in Pathways, a $24 social return on investment was generated for the broader community.”

Sue Gillespie was appointed CEO of Pathways in June 2015. One of the factors that has contributed to its success, she says, is its determination to stick to its knitting. What is different about Pathways is its singularity of focus. Our objective is graduating kids from high school. In the past I have worked in multi-service agencies. As a CEO I had to be a super generalist and expert at the same time. At Pathways we focus on breaking the cycle of poverty through education.2 She notes that it’s not always easy to maintain this focus, because of the organization’s success:

Popularity can become a challenge. When you are successful, there is pressure to expand your scope of work. Pathways has been asked about our capacity to establish new initiatives to solve other challenges—for example, to establish a new Pathways initiative for integrating new immigrants or supporting university level students. We have to ask ourselves, how many programs can we support? We cannot be everything to everyone. One of my challenges is to rein in the organization and keep us on track to achieving our strategic plan and ultimately our mission and vision.

Teri Thomas-Vanos was Executive Director of Rebound for five years, an organization based in Sarnia, ON, that was started in 1984 to try to divert at-risk youth from the court system. It has since broadened out to include over twenty different kinds of outreach and engagement services, but all with the same purpose. Every year, they deal with between five hundred to six hundred young people. Thomas-Vanos advised me that over the last thirty years or so, Rebound has received gratifying recognition—they have earned thirteen awards from the Donner Foundation, they’ve been nominated for business achievement awards through their local Chamber of Commerce, and they’ve received a Peter Drucker award.3 Furthermore, on three subsequent years, they won a “Voluntary Sector Reporting Award” from Queens University for the quality of their annual report. And they’ve received other types of recognition, including Imagine Canada’s Trustmark.

Like Gillespie, Thomas-Vanos credits mission clarity and focus as central to the success of Rebound. “Our mission and values are pivotal to the agency. Our mission drives us, and the focus on one thing is important. I love the simplicity of the mission.”

The theme of mission clarity and focus is echoed in contemporary literature about nonprofit governance. For example, Jim Collins, author of Good to Great and Built to Last, attributes the success of what he calls “great” organizations to several factors, one of which he calls the “Hedgehog Concept.”4 Organizations that observe this principle identify what they are passionate about, what they can do best in the world, and what drives their economic engine. Then they situate their mission in a locus consistent with all these factors. Says Collins, “The essence of the Hedgehog Concept is to attain piercing clarity about how to produce the best long-term results, and then exercising the relentless discipline to say ‘No thank you’ to opportunities that fail the hedgehog test.”

An example of a focused, well-crafted, outcome-oriented mission statement is that of the nonprofit called Charity: Water: “Charity: Water brings clean and safe drinking water to people in developing nations.” Other excellent examples are those from Teach for America (“Teach for America finds, trains, and supports individuals who are committed to equality and places them in high-need classrooms across the country.”), Girl Scouts of America (“Girl Scouts of America helps young girls grow into proud, self-confident and self-respecting young women.”), and the Salvation Army (“The Salvation Army makes citizens out of the rejected.”).

Crafting an effective mission statement is no easy task. It can take time to develop the appropriate language. There are a lot of poor mission statements sprinkled through the nonprofit sector that fail to inspire or provide direction. Peter Drucker is one of the most famous writers about management in North America, and his insights into issues of organization and leadership are nearly always wise and thoughtful. He has made these observations about nonprofit mission statements:

One of our most common mistakes is to make the mission statement into a kind of hero sandwich of good intentions. It has to be simple and clear. [For] a successful mission . . . you need three things: opportunities; competence; and commitment.

[Ask] first, what are the opportunities, the needs? Where can we, with the limited resources we have . . . really make a difference, really set a new standard? . . .

Then, do [the needs] fit us? Are we likely to do a decent job? Are we competent? Do they match our strengths?

[And finally,] what [do] we really believe in. A mission is not, in that sense, impersonal. I have never seen anything being done well unless people were committed.

Every mission statement, believe me, has to reflect all three or it . . . will not mobilize the human resources of the organization for getting the right things done. Nonprofit institutions exist for the sake of their mission. They exist to make a difference in society and in the life of the individual . . . and this must never be forgotten.

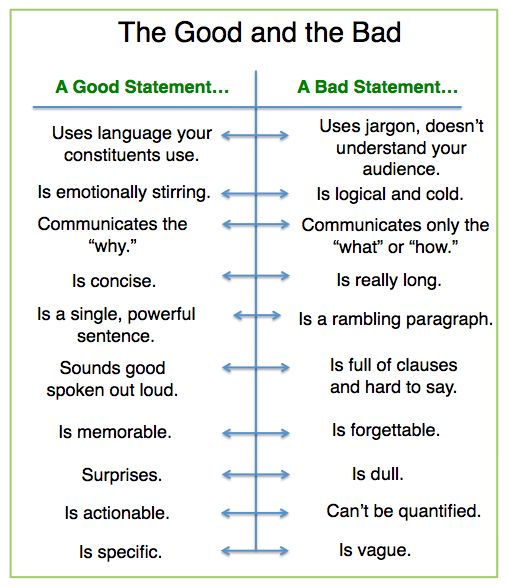

The Nonprofit Hub is an “online educational community dedicated to giving nonprofits everything they need to better their organizations and communities.” The Hub has developed a helpful summary of the attributes of good and bad mission statements.

Being Clear About Desired Results

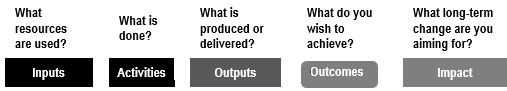

The nonprofit that wants to make sure its mission is sound needs to clearly identify the results it wants to achieve. To that end, it may be useful to make explicit the “results chain” that underpins its programs or activities.

Much writing about results chains and related concepts may be found in literature on international development and public administration that has been around in one form or another ever since the 1970s. In the field of development, this literature evolved because organizations that were funding projects became concerned about the lack of durable project results and insufficient rigour in project planning and evaluation. The literature to which these concerns gave rise is now very extensive, and a variety of methodologies have developed to help guide managers to become more rigorous in planning initiatives or assessing results. “Theory of change” is one such methodology. It is becoming increasingly well known in the nonprofit world. A similar discipline that has evolved in response to this need is known as logical framework analysis.

A results chain illustrates anticipated causal relationships between resources and activities over time (see graphic below). Increasingly, funding organizations are expecting grant recipients to show evidence that they are familiar with these ideas and that they have incorporated them into their management.

Figure 5.2 – The Results Chain

Working through a results chain or “logic model,” as it is sometimes called, for a particular program or activity can be challenging. The process gives rise to questions that may be difficult to answer, such as: What is the problem that the program is supposed to address? What is the rationale underlying program design? What assumptions have been made about the causal relationships between the various steps in the chain? What durable outcomes is the program supposed to achieve? How can results be measured? What means of verification can be used, given limited resources?

The fundamental idea underlying results-based management is that, as both Collins and Drucker have stated, an organization should have “piercing clarity” as to its mission; the mission should be articulated in terms that indicate what societal change the organization aspires to achieve, and why.

The “why” is important. Having reviewed various programs during my career, I found that program architects seldom bothered to articulate the underlying rationale—that is, the assumptions that explained why the program was necessary—or the logic that connected the program’s activities to anticipated outcomes. Perhaps they presumed that all this would be obvious; but even if the need for the program was obvious at the time of inception, things change over time. What was a compelling rationale for a program when it started may seem much less so a few years later. The lack of a program logic model may make it difficult to determine what assumptions were made about the relationship between program activities and desired results.

A well-crafted rationale provides a solid platform for a project or program; when one is lacking, the quality of programming may suffer because the rationale was not well thought through. In addition, evaluation becomes more difficult because there is no clear framework or logic model against which to assess results.

Nonprofit boards are sometimes unclear about their role. Here is an area where a board can, and should, make a valuable contribution to the work of a nonprofit. Board members who are serious about their governance responsibilities need to be asking questions about the “why” of their organization. Why is it there? What is, or should be, its value added? What outcomes ought to flow from its work? Questions such as these help to draw out what inspires the work of the organization. The answers will illuminate key decisions about priorities and how to deploy scarce resources most effectively.

Alignment

A second attribute of organizations that cope well, and which may even excel in this turbulent environment, is alignment. The idea of alignment is not new—it has been a theme in literature on organizational design for years. Alignment of programs or activities with one’s mission is another key attribute of resilient, well-performing associations.

Alignment within an organization is sometimes expressed as the concept of “fit.” Elements of the organization fit together—that is, they are characterized by complementarity and alignment. In other words, the elements are mutually supportive—there is “internal fit” among them, and in addition, they are connected to, or aligned with, the organization’s strategy. The fundamental idea is that there must be coherence among all the different elements of an organization: strategy, structure, decision processes, monitoring systems, culture, communications policies, incentives, and technology. And these must, in turn, be connected directly to the organization’s mission. The concept rejects the crude notion of an organization as a somewhat mechanistic, simple hierarchy. Rather, it envisages an organization as a more organic entity, in which the parts link together in mutual support.

In this concept, an organization is, in effect, a kind of miniature ecosystem in which the components depend upon and sustain each other. If a serious weakness exists in one part of the system, the system as a whole no longer performs as well as it could. The fit concept could also be seen as analogous to the idea of an orchestra, where each instrument has a separate score to play, but harmony only results when they play in time and in tune with each other.

The fit concept serves to remind executives that an organization won’t naturally grow unattended into an efficient productive entity. Just like a garden, it requires planning and nurturing. An organization is a complex web of individuals, relationships, expectations, structures, systems, and beliefs. There should be a plan or vision as to how it should develop that takes account of this complexity. Peter Drucker once observed, “The only things that evolve in an organization are disorder, friction, malperformance. . . . Organization design and structure require thinking, analysis, and a systematic approach.”8

The idea of alignment asserts that every organization is to some extent unique and cautions against mindless or random efforts to import “best practices” or “exemplary practices” from elsewhere. Just because an approach worked in one organization does not mean that it will be appropriate in another. The concept also stresses the integral nature of organizations. That is, since all elements of the organization are linked, what managers do in one part of the organization should be aligned with what is done in others. The objective, in building and managing an organization, is to get its elements working together in harmony to increase productivity. If they are not integrated, they will either drag the organization off course or dampen (or even nullify) each other’s effects. The framework, or “glue,” to hold the different components together and align them should be provided by the organization’s mission and strategy.

If an organization does not seem to be performing well, the fit idea cautions its board or executive director not to jump to the conclusion that what is required is a reorganization—a structural change. Many managers seem overly impressed with the ability of structural change to improve the way an organization performs, and they are insufficiently heedful of how other factors may be the cause of the organization’s problems.

When there is harmony among the different components of an organization, and they are well aligned with each other, the organization becomes a more integrated, efficient entity, and thus better equipped to cope with external turbulence. Think of the hull of a well-designed boat: a sleek design enables it to navigate waves and other types of turbulence more effectively.

Refocusing and Cleaning House

The concept of alignment as well as the ideas about mission discussed above have a corollary. Contrary to what some may believe, a mission should not be static. It should probably not be carved in stone. If a mission is designed to confront real needs, if it is “actionable” and actions are being taken to pursue it, then we might hope that, with the passage of time, the needs will be addressed, or they may evolve. Likewise, new, more effective ways of pursuing the mission may come to light, because of feedback from the field, because of insights gathered from other organizations, because new staff with new capabilities are recruited, because of possibilities offered by technological innovation, or other reasons.

Resources are always tight in the nonprofit world. Given the financial challenges inherent in the current environment, the intrepid nonprofit needs to make sure that scarce dollars are used as efficiently as possible. To maximize impact, a nonprofit needs to be prepared to take stock periodically of existing programs or projects and, if necessary, shed those that are less effective in favour of new ones that promise better results. That is, the nonprofit that is serious about maintaining its focus and achieving results needs to be prepared to do intermittent housecleaning, getting rid of activities or programs that have outlived their usefulness. In addition, as time passes and circumstances change, there may be a need to review and recalibrate the mission itself.

To read more, get The Intrepid Nonprofit: Strategies for Success in Turbulent Times from Civil Sector Press here

“History,” Pathways to Education (2018). https://www.pathwaystoeducation.ca/history

Author’s interview.

Jim Collins, Good to Great and the Social Sectors (New York: Harper, 2005).

Peter Drucker, Managing the Nonprofit Organization, Principles and Practices (New York: HarperCollins e-books, 1990).

Matt Koenig, “Nonprofit Mission Statements: Good and Bad Examples,” non-profit hub (2013), accessed August 7, 2018. https://nonprofithub.org/starting-a-nonprofit/nonprofit-mission-statements-good-and-bad-examples/

Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Results Management in Norwegian Development Cooperation: A Practical Guide (2008), accessed August 7, 2018 https://www.norad.no/globalassets/import-2162015-80434-am/www.norad.no-ny/filarkiv/vedlegg-til-publikasjoner/results-management-in-norwegian-development-cooperation.pdf

Peter F. Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (New York: Harper and Row, 1973), 523.